|

|

|

|

Traditional Religious Masks

BY: SUN STAFF

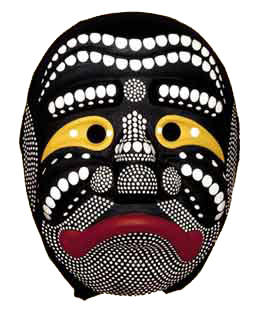

Lord Nrsimhadev Mask, Nepal

Dec 21, DELHI, INDIA (SUN) — Excerpts from an article on traditional religious mask restoration by R. Jain.

The tradition of making masks is common to almost all civilizations the world over. Simply defined, a mask is a form of disguise, an object that is frequently worn over or in front of the face to hide the identity of a person and assume the identity of another being. Beyond the superficial, the mask has other functions - social, communicative and religious. Masks are part of the religious rituals in several societies, hence restoring masks was not a routine technical work -- it meant bringing back traditions, rituals and symbols.

Masks are made of a variety of materials, depending on the local availability of materials. Some are intended for temporary or short-lived purposes and are made from leaves or coconut, such as the Theyyam of Kerala. The longer lasting ones, used repeatedly during festivals and rituals, may be made of woods, metals, shells, fibres, ivory, clay, horn, stone, feathers, etc.

An amazing rare collection of masks from the world over has been collected by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Art (IGNCA). The preservation or disposal of masks is decreed by tradition. Many masks and often their form and function are passed down through clans or families, and they are usually spiritually reactivated or aesthetically restored by repainting and redecorating without destroying the basic form. A few masks from Nepal in the IGNCA collection were accidentally damaged and sent to the conservation laboratory. Hence it was imperative to study the technique of mask making of Nepal in order to properly restore them.

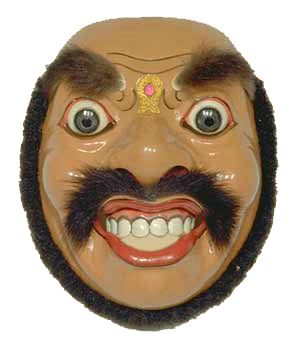

Masks of some kind or other are made in almost all the regions of Nepal, but masks used for ritual dances are made only in the Kathmandu valley and Solu-Khumbu area in the Northern region. The Nrsimhadev mask shown above comes from this region. Nepalese ceremonial masks are made in accordance with traditions, in some cases once every year and in other cases once in twelve years. As most of the mask dances originated in the medieval age (15th to 18th C A.D.) in Nepal, it can be assumed that the mask making craft also originated during that period. Nepalese masks are generally made for their use in the performing arts, but some of them have close relationship with popular folklores. Masks used in ritual dances have special meanings and significance in forms and designs, which vary from one another.

Clay, cotton, paste or glue, wooden board, wooden mould, water, local paper, jute and colours are the essential raw materials for Nepalese masks. For ritual masks, local clay, known as dyaca, is used. This is unlike the ordinary soil, being black in colour and having profound plasticity and strength.

The process of making masks for religious purposes is regulated by rituals, which sanctify the materials. Then the artist spends hours pounding and kneading the first clay. When it becomes plastic or workable, it is ready for forming. Then the individual lumps of clay are placed on wooden boards, pounded with a mallet, and rolled into flat oblong shapes. The thickness varies according to need. This is then gently placed over a low relief mould locally known as thasa of the select Deity. Thasa has already been covered with a clean black cloth of fine quality to prevent clay from sticking to the mould.

The mask makers gently press the flattened clay with their fingers so that it conforms to the contours of the mould. As the mould is in low relief, excess clay from the sides is used to build up prominent features of the mask. After flattening the clay in the mould properly, the artist builds up the features of the mask like the nose, eyes, lips, etc. He smoothes the entire mask with water and cuts the overlapping sides to fit the contour of the mould. Then the clay mask forms are left to dry in the shade on the moulds for about four days. When it becomes dry enough to retain its shape, the commissioned mask is carefully lifted off the mould holding the four corners of the black cloth.

When fully dry, they are painted with a mixture of boiled wheat flour, water and glue which dries to an almost opaque finish. This glue is first applied to the back of the masks and covered with large pieces of jute. The jute backing gives the masks additional strength and prevents them from curving inwards. At certain points at the top and on the sides of the masks, two holes about half an inch apart are made and a strong rope, about one eight of an inch thick is drawn through. This is used to fix the masks on the dancers. To make the interior of the mask smooth, a layer of cotton cloth is glued to the jute.

The same glue is next applied to the front of the mask and strips of cotton cloth, carefully cut to fit the contours of the mask, are glued in place. When the cloth strips dry, low-grade Nepalese paper is glued, to give it an even and smooth finish.

After the glued surfaces have dried, which takes about a day, the mask-makers apply a white mixture to the face of the mask. The white pigment acts as a primer, a ground and a base colour; it dries within five minutes. When the final application has dried, the face of the mask is sanded with natural jute fibres. This works like a fine grade of steel wool to give the surface an even smoother finish. Now the masks are ready to be painted. All the pigments are mixed with animal glue, which liquifies when heated and are thinned with water. Colour in the commissioned masks is primarily symbolic. Specific manifestations of moods of different Deities are colour-coded so that the non-initiates can recognize them. Surface treatments range from rugged simplicity to intricate carving and from polished woods and mosaics to gaudy adornments.

The mask-makers produce masks in their houses during the day. The ritual masks are generally made by one special caste known as Chitrakars among the Newars of the valley and Lama priests among the Sherpas of the northern region. Knowledge of mask-making is communicated from father to son, from master to disciple by formulae or mantras recited in their mother tongue.

Pictured above are numerous kinds of Indian religious masks, not only from the Nepal region, but elsewhere around the subcontinent.

| The Sun |

News |

Editorials |

Features |

Sun Blogs |

Classifieds |

Events |

Recipes |

PodCasts |

| About |

Submit an Article |

Contact Us |

Advertise |

HareKrsna.com |

Copyright 2005, HareKrsna.com. All rights reserved.

|

|