Temple Cities of South India

BY: A. NANGIA

North Gopuram, Minakshi Temple

Oct 14, PURI, ORISSA (SUN) — South India's temple architecture.

Gopuram

The Gopuram (literally Cow-Gate), was erected primarily to emphasize the importance of the temple within the city precincts without in any way altering the form of the temple itself. The formal aspects of the Gopuram were evolved slowly over time. It had to be towering, massive and impressive. But it was not felt necessary to repeat verbatim the square-based form of the temple Vimana. This could be due to the fact that the square was a essentially a static form, signifying calm and rest, while the entrance gateway needed to have some dynamism. Elongating the square and converting into a rectangle with an open entrance in the middle solved this problem. Above this base could be raised tier upon tier of a pyramidal structure comprised of brick and plaster with the topmost tier also a rectangle, albeit much smaller.

This rectangular top was crowned by a barrel-vaulted shape of Buddhist origin, crowned with a row of finials. As time went by, cities all over South India could be discerned from afar by the distinctive shape of their Gopurams dominating the skyline. The temple-city had evolved from a place of pilgrimage to the hub of political, cultural, social and secular activity of the region.

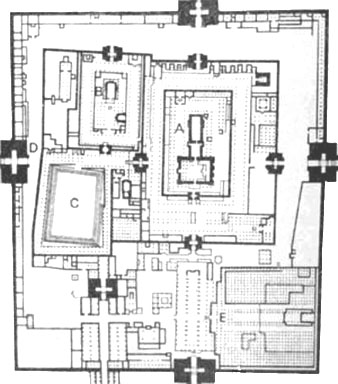

The 'Annular' Growth of Cities

Such an increase in importance of the city led to a natural population increase as well as demands for more resources. But growth was also constrained by the huge battlements thrown up around, punctuated by the massive Gopurams. The only viable solution was to erect yet another wall around the existing one. The new wall, too, had its own huge Gopurams. In this way the city grew much like the annular rings of a tree, with successive perimeters being added as population growth dictated. Thus, the great temple of Srirangam at Tiruchirapalli acquired several concentric rings of growth over a period of 500 years. Ultimately, the concentric city and Gopurams, which evolved out of necessity rather than conscious design, came to be accepted as the standard 'form' of temple construction in the south.

The Meenakshi Temple at Madurai

Thus it came to pass that the Meenakshi temple was designed as a series of concentric courtyards, or parikramas. The spaces around the shrine became hierarchical, diminishing in religious value; the further one went from the main shrine. The outermost ring had buildings of a more practical nature - accounts, dormitories, kitchens, shops selling items for rituals, maintenance areas and 'parking' for the increasing number of chariots.

The inner circles contained parikramas for singing and religious tales, bathing tanks and guest houses. And in the innermost courts were the pavilions for the dancing girls and the treasury - both jealously guarded by the priests! Admittance was restricted to the upper castes only. And finally, the holiest of holies, the Cella containing the idol of the deity was open only to the head pujari and out of bounds for even the king of the land.

The Hall of a Thousand Pillars

With temple building losing its architectural challenge and becoming more and more a town planning exercise, the craftsman was restricted to working on pavilions, halls and Gopurams, the last of which grew ever larger and imposing. The huge hall in the Meenakshi temple needed 985 pillars to support its roof. This is the famous 'Hall of a Thousand Pillars'. Unfortunately its size cannot compensate for its architectural mediocrity, and according to Satish Grover:

…the hall, surely one of the more arid products of Indian craftsmanship is a museum of drawings and photographs of the entire gamut of the 1200 years of temple architecture of the South. [1]

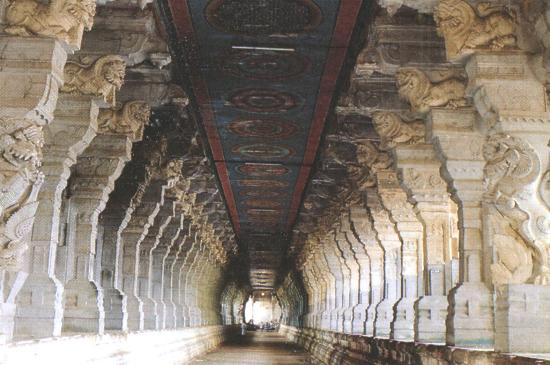

The Corridors of Rameswaram

Rameswaram, on a tip of land jutting out into the sea, is a maze of huge pillared verandahs. Not only is the temple surrounded by corridors, but it is also linked to the entrances by covered passages. Rameswaram thus has the distinction of possessing the longest corridors in the world.

However, in spite of their huge proportions, the Gopurams and pillared corridors were the last gasp of conceptually revolutionary Hindu architecture in the country. The invasion of Islam had already resulted in the North being a bustling hive of mosque and tomb building. The Hindu stonecutter proved to be equally adept at carving Islamic masterpieces as sculpting nubile forms on the surface of temples.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Grover, Satish The Architecture of India - Buddhist and Hindu, Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. , New Delhi, 1980.