How Little Americans Know About Religion

BY: TOM KRATTENMAKER

May 1, CANADA (USA TODAY) — It has been a season of consternation about the religious illiteracy of America. Prompting fresh knowledge of our ignorance is Stephen Prothero's new book, Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know - And Doesn't. The book cites research showing that even Christians are poorly acquainted with the Bible. Familiar with Benjamin Franklin's aphorism "God helps those who help themselves"? Three-quarters of us, Prothero reports, wrongly believe it comes from the Bible. Only one-half of us can name one of the four gospels of the New Testament. (For the record, they are Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.) Only a third can identify who delivered the Sermon on the Mount. (Answer: Jesus.)

The worry about religious illiteracy is well justified given the powerful influence of faith on American culture and politics. So it's understandable that we're also witnessing a renewed determination to teach about religion in public schools. The Georgia Legislature has approved a law allowing the teaching of the Bible in public schools. According to a recent Time cover story endorsing Bible instruction, public-school courses on the Bible, while far from numerous, are increasingly popular around the country.

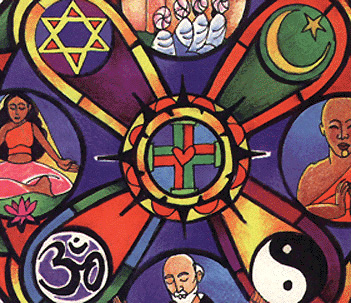

That's all well and good, provided the curricula and instructors respect the crucial difference between promoting religion and teaching about religion. But here's a suggestion that will test our seriousness about developing religious literacy in this country. Let's also teach about Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism and the world's other major religions. Especially, let's teach students about Islam.

Out of sight in Oregon

The necessity of learning about the world's second most-popular religion was driven home for me on a recent visit to a small Muslim K-8 school in Oregon, operated by the Muslim Educational Trust. I initially noticed the conspicuous absence of an address - even a city - on the school's website. Upon arrival, I was struck again by the school's deliberate obscurity: Tucked behind a fence, it bore no sign and gave no indication whatsoever that students and teachers (many of them Caucasian, incidentally) were busy at work behind its non-descript white walls.

You can guess the reason why the school keeps its profile low. Islam is reviled in many quarters, equated with terrorism and iron-clad theocracy. Muslims and their mosques have been the targets of occasional violence and vandalism since the 9/11 attacks, and polling data show that nearly half the American public harbors negative views of Islam.

Muslims and their faith are also on the receiving end of some harsh rhetorical attacks. Consider evangelical Christian leader Franklin Graham and his notorious post-9/11 comments about Islam - a "very evil and wicked religion," in the estimation of Graham, the son of the revered evangelist Billy Graham and the man who delivered the invocation at President Bush's first inauguration. Also joining in the tarring-and-feathering of Islam is author Craig Winn, who has argued that the war on terror should be reconceived as the war on Islam because, as Winn sees it, terrorism is not a misapplication of the Muslim faith but its truest expression.

Awash in these negative images of Islam, I found it fascinating to see a different face of Islam as I toured the Oregon school and listened to Wajdi Said, the executive director of the Muslim Educational Trust. Said, who has lived in this country for almost 20 years, contends that Americans dwell in near-complete ignorance of Islam, especially what it teaches about relations with other religions.

"The Islamic faith accepts the marriage of Muslims to Christians and Jews," Said points out. In fact, Said adds, Islam's history with other faiths hasn't always been adversarial. Just the opposite, he says.

"Christianity and Judaism flourished under the protection of Muslim leaders through most of our history. We have a great history, and a great faith that accepts everybody. We need to educate Americans about the loving and caring face of Islam," Said says.

Unfortunately for Said and his colleagues, it's a different face of the religion we tend to see in the West today - Islamic fundamentalists committing violence in the name of their faith and supposed followers of the prophet shouting their hatred of "infidels." The emergence of al-Qaeda and its leader, Osama bin Laden, only reinforces the dangerous face of Islam. The slaying of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh. Riots over the publishing of the prophet Mohammed cartoons. The list goes on. Scholars and pundits may debate the scriptural legitimacy of these expressions of the Muslim faith. But there's no denying Islam's image problem in the West.

How to counter that with appreciation for the hundreds of millions of Muslims who go about their business and religious practice in peace? It all points back to education. Thankfully, many U.S. colleges and universities have programs in Islamic studies and Arabic-language instruction. But while higher education is responding to the national need, "we have a long way to go" when it comes to teaching about Islam in America's public schools, says Charles Haynes, who directs public education programs for the Freedom Forum's First Amendment Center in Arlington, Va. Teaching effectively about the Muslim faith, according to Haynes, has become all the more difficult post-9/11, in part because of conservative political pressure.

From a practical standpoint, teaching about Islam offers compelling benefits for effective military and diplomatic strategy. The world is "aflame in faith," as Yale University professor Jon Butler has written. The men and women of the U.S. military tend to know little about religions other than their own, Butler notes, "yet they have been asked to fight wars in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Iraq over the past 15 years in which religion has stood at the very center of each conflict."

A hopeful view of the world

Call it extreme optimism, but it is my hope that greater understanding of the world's religions could eventually make the military argument moot. Understanding can lead us away from seeing only the worst in our ostensible "enemies," and away from the religion-fueled violence that scars our time. Maybe hope can be drawn from a change that's about to happen at Said's school. Anti-Muslim sentiment has calmed to the point where he feels he can finally mount a sign at the small campus, and he is moving ahead with plans to do precisely that.

Is it true that "Islam is peace"? That's as over-simplified as saying Islam is inherently violent. In truth, the essence of Islam is a complex and contested issue. Much the same could be said about Christianity.

Yes, let's teach our students about the Bible. But if we're going to offer the kind of education that can make a difference in our divided world, let's not stop there. Let's make sure our students go into the world with some understanding of the Quran.

For more informatoin see Americans get an 'F' in religion -- what's your score?

Tom Krattenmaker, who lives in Portland, Ore., specializes in religion in public life and is a member of USA TODAY's board of contributors.