The Caste System in Bengal

BY: SUN STAFF

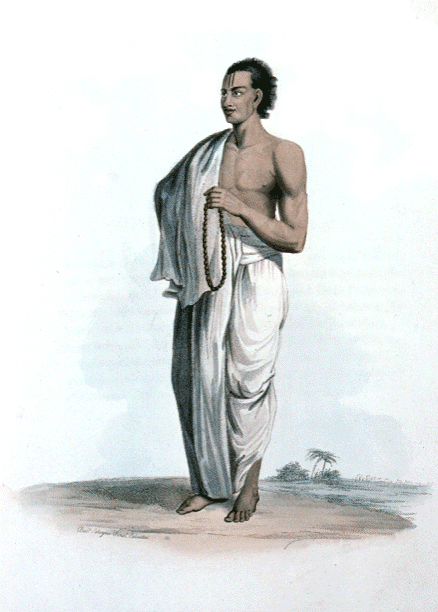

Bengali Brahman

Solvyns, Hand-colored Lithograph, c. 1799

Jan 23, CANADA (SUN) — A three-part series on the varnasrama system in Bengal, with a pictorial study of the various varnas and asramas.

While formally there are four castes in Vedic culture: brahmins, ksatriyas, vaishyas and sudras, the social reality of this structure is very different in certain parts of India. The social rules enjoined by various religions also differ in different regions of Indian subcontinent. In Bengal, much of the development of the first distinct Bengali Hinduism took place during the rule of the sena and barman kings, and is described in the writings of Bhavadeva, Aniruddhabhatta, Vallalasena, Laksmanasena, Gunavinsu, Halayudha, etc., as well as in the Brhaddharma and Brahmavaivarta Puranas.

To a large extent, they codified, formalized and made immutable some of the existing social structure, as well as making it very much more rigid. In fact according to traditional stories, which must be distinguished from history, brahmins originated in Bengal during this time.

The society described therein does not contain (though they still appear in origin myths) any ksatriyas or vaishyas, except when some of the rulers are referred to as kshatriyas. Today, most of the people who call themselves ksatriyas have variations of varman or malla as their surname, and some jewelers claim descent from the vaishyas.

The brahmins were divided geographically into Radhi and Barendri, with a variety of village associations, but according to Aniruddha, they had forgotten their Vedic tradition. The Radhis are divided into Kullnas and Vamshajas, and the Barendras into Kullnas and Kaps. The Kulins are organized into 56 villages and 36 mels and thaks like phule, vallabhi, kharda and sarvanandi.

In addition, there were Vaidika Brahmins who came (according to tradition during Shyamalavarma's rule) from the north, including Sarasvati region, and from the south, including Utkala, India. According to Halayudha, these were the only brahmins who knew the Vedic tradition. They were organized as a pashcatya and a daksinatya group.

Mention is also found of brahmins from Shakadvipa who, according to tradition, came during Shashagka's rule. They were called Grahavipra. The latter, according to Brahmavaivarta Puranas, however, are children of devalas, who are true Shakadvvipi brahmins, and vaishya women, who were not respected in society. A subcaste of them called agradani used to perform shraddha ceremony for the shudras. Also found is another group of brahmins not recognized in society: the bhatta brahmins, presumably related to the Bhattacharyas.

According to the rules developed in this period, the respected or shrotriya brahmins could not perform priestly duties for anyone other than the 20 high shudra subcastes. According to Vrhaddharma Purana, these shudra subcastes arose from a mixture of castes forced by King vena. The upper subcastes had parents belonging to unmixed caste, the middle ones had fathers of unmixed caste, and the lowest had both parents of mixed caste.

Those who violate the rule get the subcaste of that person and thus were found, in addition, varna brahmins who could not even serve water to the true brahmins. In additions, certain occupations like teaching sudras, doing priestly duties for them, practicing medicine or astrology, or performing painting or other artistic activities, were forbidden; although certain others like farming and fighting, or working as a minister, go-between, religious leader or general were all allowed.

The rules developed in this period prescribe strict limits on brahmins intermixing with the rest of the society. For example, they were not allowed to eat food cooked by sudras, except for fried items, rice cooked in milk and in time of distress. However, they could not drink even water touched by the untouchables, neither could they be touched by untouchables. Elaborate rituals were needed to clean oneself of violations of these rules.

Similarly, even though intermarriage between upper caste men and lower caste women was allowed, the normal rule was marriage within one's own caste. Rules made it clear that a wife of a lower caste had less rights than one of the same caste. Marriage rules for brahmins, and possibly upper category of sudras, had to follow the endogamy/exogamy rules of sapinda (exogamy for parts of an extended family), sagotra (exogamy for a group of paternally inherited markers called gotra) and samanapravara (exogamy outside related gotras).

Marriage was also forbidden if it took place according to high ceremony and any of the seven male ancestors along the father's line and five along the mother's line coincided. Low marriage ceremony only required exclusion for five and three generations, but pushed one to the sudra caste.

Even the Kayastha Kullna rules are complicated today. The first three sons who married had to obey rules to stay in the caste, whereas the fourth (madhyamsha dvitiya), fifth (kanisthya), and the younger (vamshaja) ones had laxer rules, as they were not considered as high in caste status: they traditionally married elder maulikas.

Note that this does not imply that the Bengali society, either before or during the Sena period, was very spartan or puritanical in the modern sense of the word. Though brahmins marrying sudra women was looked down upon, extra-marital relationships between them were overlooked.

Although this structure can clearly be seen in Bengal even today, there is great variation to be found as we move across the different districts of Bengal. For example, the Kayasthas who were the top of the non-brahmin hierarchy are differently rated in places like rural Bakura, Virabhuma, Varddhamana, and MedinipUra, where the farming sadgopas are at the top of the hierarchy.

The advent of Vaisnavism in the middle ages also led essentially to a new caste, which was to be reviled by the traditional society. The cult of Caitanya Mahaprabhu was, at its heart, little interested in the confines of castes. Mahaprabhu welcomed all the fallen conditioned souls, imploring them to put aside concerns of bodily conception and take up the chanting of the Holy Name.

Excerpted from A Short History of Bengal, by Tanmoy

The Sun

News

Editorials

Features

Sun Blogs

Classifieds

Events

Recipes

PodCasts

About

Submit an Article

Contact Us

Advertise

HareKrsna.com

Copyright 2005, HareKrsna.com. All rights reserved.