|

|

|

|

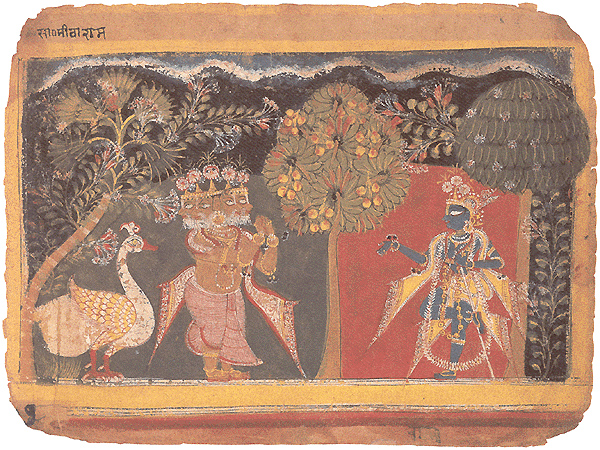

Intimate Worlds Oct 2, CANADA (SUN) — Krsna Consciousness in Art Criticism. An extraordinary collection of eighty-eight Indian paintings was recently donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Dr. Alvin O. Bellak, a private collector and clinical psychologist who lives in that city. Over years of collecting, Dr. Bellak had gathered an amazing group of pieces, many with Vaisnava themes. In the opening chapter of Intimate Worlds, a book showcasing the collection, PMA curator Darielle Mason writes: "In many ways the illuminated books (whether bound or loosely grouped) and the individual paintings and drawings that originated in the court workshops of the Indian subcontinent are like jewels. As portable luxury goods, both types of objects are treasured for their artistry, their fine colors and polished finishes, their status as courtly accouterments. Over the years, both have been given as gifts to commemorate political alliance, included as parts of dowry settlements, seized as booty in conquest, amassed into royal treasuries, sought after by collectors, preserved and exhibited through the world. Yet where paintings differ from jewels is in the level of intentionality of their creation. A painting is not a found natural object enhanced by the craftsman; it is entirely a work of artistry - pulp to paper, mineral to paint. And, unlike a jewel, the primary original aim of these works, whether a religious epic or a portrait, was to tell a story. Yet to focus solely on the point of creation of paintings - on the painter, patron, and original meaning - is to ignore a great and intriguing part of their history." As one typically finds in a book of mundane art criticism, the art experts who authored this book have a great deal of academic understanding of Indian art, but only a rudimentary understanding of the spiritual philosophy that underlies every stroke of the artist's brush. In Intimate Worlds, three expert art critics were engaged to write essays about the Bellak Collection. Each took a different approach, all of which are interesting from an art history standpoint. Ms. Mason describes the essays by saying: "…these short studies seek to explore through a historical perspective the question of the meaning of "quality" to the various individuals who have made, used, and owned these works of art. What aspects of these paintings were most valued at any point in time? How did notions of value change? What made one work more desirable than another? How was - and is - a hierarchy of taste established, and what might these hierarchies imply?" She explains that one essayist used the monetary values written on the paintings themselves to gauge their perceived value and to get a sense of the 'hierarchy of taste' among the courtly cultures who held them in the Rajasthani courts or imperial Mughal treasuries. While these essayists present three uniquely interesting ways to approach and discuss Indian art, none get to the essence of Bhakti represented in the many Vaisnava paintings included in the Bellak collection. In this and future articles, I will attempt to round out the curatorial descriptions provided with these paintings by adding a little more Krsna Conscious commentary, beginning with the above work entitled "Brahma Honors Krishna". This manuscript page is from a dispersed series of the Bhagavata-Purana done in Northern India, probably in the Delhi-Agra region, c. 1525-40. The painting was rendered in opaque watercolor and ink on paper. In order to understand the essence of this painting, we should first consider the elevated status of the Bhagavata-Purana from which this manuscript illustration came. Bhagavata Purana, or Srimad-Bhagavatam, is the jewel of the Puranas and is one of the most prominent texts accepted by Acaryas in the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya. The Bhagavatam provides histories of the prominent Visnu avataras and the lives of the Supreme Lord's great devotees, and presents the essence of Krsna Cconscious philosophy. Srimad Bhagavatam came down through the disciplic succession, as explained to Narada Muni by Lord Brahma, who is himself featured in this painting: "Whatever I have spoken to you about the Bhagavatam was explained to me by the Supreme Personality of Godhead, and I am advising you to expand these topics nicely so that people may easily understand the mysterious bhakti-yoga by transcendental loving service to the Lord." Srimad-Bhagavatam 2:9:35 Purport Intimate Worlds describes the scene which preceded the one depicted in the painting, "Brahma Honors Krishna": "This painting, which falls at the beginning of the fourteenth chapter, marks the culmination of an episode that leads the god Brahma to acknowledge Krishna's limitless existence. Having witnessed Krishna perform one supernatural feat after another, Brahma tests him once more, this time by employing magic to abduct a group of cowherds and their kine from Krishna's presence. Krishna recognizes Brahma's handiwork when he is unable to locate the missing cows and cowherds, and simply multiplies himself to replicate each one. The replacements resemble the original cows and cowherds in every detail, but they so strongly embody the divine presence that their mothers' affection for them grows exponentially. This remarkable development and Brahma's subsequent vision of each figure being transformed into Krishna in all his splendor moves him first to marvel at Krishna's ability to transcend his own deception and then to recognize the deity's omnipresence. With this, he dismounts his swan vehicle and prostrates himself before Krishna. Raising himself to his feet, Brahma joins his hands together in veneration, and begins a long hymn of praise to Krishna." In Chapter 13 of Krsna Book, Srila Prabhupada describes the pastime wherein Lord Brahma hides the cows, and Sri Krsna expands Himself innumerably as the cows and cowherd boys so as not to agitate the minds of the mothers, who would be so upset if Krsna returned home alone without his companions. Srila Prabhupada provides the essence of this pastime, which establishes the supremacy of the Lord: "In the Vedas it is said that the Supreme Personality of Godhead has expanded Himself in so many living entities by His energy. Therefore it was not very difficult for Him to expand Himself again into so many boys and calves. He expanded Himself to become exactly like the boys, who were of all different features, facial and bodily construction, and who were different in their clothing and ornaments and in their behavior and personal activities. In other words, everyone has different tastes; being an individual soul, each person has entirely different activities and behavior. Yet Krsna exactly expanded Himself into all the different positions of the individual boys. He also became the calves, who were also of different sizes, colors, activities, etc. This was possible because everything is an expansion of Krsna's energy. In the Visnu Purana it is said, parasya brahmanah saktih. Whatever we actually see in the cosmic manifestation--be it matter or the activities of the living entities--is simply an expansion of the energies of the Lord, as heat and light are the different expansions of fire." Given the above explanation of Lord Brahma's pastime with Sri Krsna and the cows, we must consider the painting to be an expression of the fundamental philosophical truths represented by this lila pastime. In other words, we can see in the color, line, texture and vibrancy of the painting an expansion of the Supreme Personality Himself in every living thing: Lord Brahma, his vahana carrier, the trees and creepers - even the dark clouds that frame the painting. Everything in the cosmic manifestation is the product of this Divine Source. In this pastime, rather than expanding Himself as paramatma in everyone's heart, the Lord expanded Himself as a portion of the calves and cowherd boys. Srila Prabhupada goes on to explain that eventually, Lord Brahma returned to the scene of his prank. In this passage from Krsna Book, Srila Prabhupada discloses the absolute truth demonstrated by Lord Brahma's use of mystic powers in making the cows and cowherds disappear: "Brahma came back to see the fun caused by his stealing the boys and calves. But he was also afraid that he was playing with fire. Krsna was his master, and he had played mischief for fun by taking away His calves and boys. He was really anxious, so he did not stay away very long; he came back after a moment (of his calculation). He saw that all the boys and calves were playing with Krsna in the same way as when he had come upon them, although he was confident that he had taken them and made them lie down asleep under the spell of his mystic power. Brahma began to think, "All the boys and calves were taken away by me, and I know they are still sleeping. How is it that a similar batch of boys and calves are playing with Krsna? Is it that they are not influenced by my mystic power? Have they been playing continually for one year with Krsna?" Brahma tried to understand who they were and how they were uninfluenced by his mystic power, but he could not ascertain it. In other words, he himself came under the spell of his own mystic power. The influence of his mystic power appeared like snow in darkness or a glowworm in the daytime. During the night's darkness, the glowworm can show some glittering power, and the snow piled up on top of a hill or on the ground can shine during the daytime. But at night the snow has no silver glitter; nor does the glowworm have any illuminating power during the daytime. Similarly, when the small mystic power exhibited by Brahma was before the mystic power of Krsna, it was just like snow or the glowworm. When a man of small mystic power wants to show potency in the presence of greater mystic power, he diminishes his own influence; he does not increase it. Even a great personality like Brahma, when he wanted to show his mystic power before Krsna, became ludicrous. Brahma was thus confused about his own mystic power." The pastime comes to a close with Lord Krsna having great compassion for the bewildered Brahma, and again pulling the curtain of yogamaya over the scene, He relieves Brahma from his great perplexity. "Immediately Brahma descended from his great swan carrier and fell down before the Lord just like a golden stick. The word used among the Vaisnavas for offering respect is dandavat. This word means "falling down like a stick"; one should offer respect to the superior Vaisnava by falling down straight, with his body just like a stick. So Brahma fell down before the Lord just like a stick to offer respect; and because the complexion of Brahma is golden, he appeared to be like a golden stick lying down before Lord Krsna. [ ] After repeating obeisances for a long time, Brahma stood up and smeared his hands over his eyes. Seeing the Lord before him, he, trembling, began to offer prayers with great respect, humility and attention." In Chapter 14 of Krsna Book, the "Prayers Offered by Lord Brahma to Lord Krsna" begin: "Brahma said, "My dear Lord, You are the only worshipful Supreme Lord, Personality of Godhead; therefore I am offering my humble obeisances and prayers just to please You. Your bodily features are of the color of clouds filled with water. You are glittering with a silver electric aura emanating from Your yellow garments." By the mercy of the pure devotee's instruction, we can understand the true meaning behind Lord Brahma's pastime with Krsna and the cows. Lord Brahma has been benedicted by Krsna, who arranged it so that Brahma had an opportunity to recognize the Lord. Of course, the writers of Intimate Worlds don't emphasize the fact that Krsna is God and Lord Brahma is his great devotee. There is also no distinction made as to the fact that Brahma is a demigod, not a "god" himself. The absence of this clarification unfortunately helps to perpetuate the bewilderment that leads to a perception of Hindusm as a polytheistic religion. While the writers of Intimate Worlds did not present the absolute truth represented in this painting, they do an excellent job of technically describing the painting in detail: "The artist pays tribute to the momentousness of the revelation by isolating each of the deities within a separate colored field. The stout, four-headed Brahma appears against a cool green background; Krishna, the object of his devotion stands opposite, his superiority indicated not only by his receptive gesture, but also by the brilliant red rectangle positioned immediately and exclusively behind him. Krishna's theological advantage is carried through even to the trees that bracket and divide the two figures. Whereas Krishna stands erect on one leg between two trees with absolutely straight trunks, Brahma is backed by a date tree whose trunk bends close to him and his vehicle as if in imitation of his earlier prostration. A black sky and an undulating band of clouds set off the trees' luxurious foliage and a flowering creeper, which entwine in the upper reaches of the composition to bind the two halves together. The result is a painting whose masterful design matches its religious eloquence." The golden brown tree trunks of the mango tree and the flowering tree behind Krishna not only bracket the two aspects of the painting, they also frame the red background making a regal, temple-like setting for the Lord. As we see in Gita Govinda images, red also indicates action in a panel, or the location in the painting where the most important activity is taking place. We also read the description from sastra of Brahma falling down at Lord Krishna's feet to offer his obeisances, looking just like a golden stick, and we can see the symbology of dandavats in the golden trunks framing Krishna in this painting. In Intimate Worlds, the writer mentions the "flowering creeper which entwine in the upper reaches of the composition to bind the two halves together". The spray of foliage above Krishna's head is quite similar although perhaps more opulent, than the foliage directly above Lord Brahma's head. This unity of space in which the two meet is the transcendental pastime itself. While the writer describes the "flowering creeper", it is interesting to note that the foliage above Krishna's head actually appears to be from a date tree, resembling quite identically the clusters of the date tree above Lord Brahma's head. Yet we see no trunk or canopy of the date tree on Krishna's side of the panel. Rather, we see a rather mysterious creeper of date-like foliage to the right of the tree trunk behind Krishna. This might also be seen to symbolize the Lord's phenomenal potencies. The writer uses an interesting turn of phrase in describing this placement as an indication of "Krishna's theological advantage". In some regards, the philosophical advantage might be said to lie with Lord Brahma, who has been benedicted by Krishna, and who has the benefit of acting in the capacity of the worshipper - a rasa that is described as being more potent than even being the object of worship, particularly in the context of Radha and Krishna. The writer then points to "Krishna's receptive gesture", describing His upturned hand of invitation to Brahma. We can also see in this element that the Lord is offering his respects in return to Lord Brahma. Krishna is standing on one leg, a posture that typically indicates renunciation. In this context, it can be seen to represent Sri Krishna having gone to the effort of giving this great benediction to Brahma. With one hand extended, Krishna holds his cowherd staff in the other hand. This is a familiar piece of paraphernalia for the cowherd boy. The writer has explained that "Brahma is backed by a date tree whose trunk bends close to him and his vehicle as if in imitation of his earlier prostration." There is also a sense of shelter here, not unlike Sesanaga, the great serpent who towers over and protects Lord Visnu. The Lord accepts his devotee, doesn't reject him, even though Brahma questioned the Lord's potencies. Again, that visual symbol of shelter is the very same that is above Krishna's head, indicating the reciprocation of the worshipper and worshipped, who give one another shelter in their reciprocal loving exchanges. The name of Lord Brahma's vahana (carrier) swan is 'Hamsa'. In the painting, the shape of Hamsa's crown feathers is similar to the date tree sprays, and the artist masterfully places one spray horizontally behind the Swan's head. There is just a little grass in the picture, placed directly beneath the vahana. This gentle artistic touch may have been intended to represent the fact that Krishna provides all the living entities with their basic requirements. The highly stylized clothing elements contribute a great deal to this remarkably beautiful painting. In contrast to the roundness of the trees and the swan vahana, these sharply pointed pieces of cloth create dramatic tension, and also a sense of the seriousness of the scene. In the prayers offered to the Lord by Brahma, he described Krishna's beauty in this way: "Your bodily features are of the color of clouds filled with water. You are glittering with a silver electric aura emanating from Your yellow garments." The artist has faithfully represented Brahma's words, showing Krishna in a strikingly beautiful yellow dhoti and shawl. The sharp corners and lines extending from the tips indicate the 'electric aura' emanating from the Lord. While both Brahma and Krishna wear very beautiful garb, Krishna's is fittingly more opulent. Brahma's dhoti is actually quite plain, though his shawl is highly ornamented. Lord Krishna's opulence is also marked by his flowing garlands and jewelry. The Lord is fully resplendent in opulently decorated crown and striking tilaka, while Lord Brahma's crown is more subdued (although, of course, he wears four crowns!) Lord Brahma is also wearing beautiful jewelry and tilaka. We see what appears at first glance to be a technical flaw in this painting, in the position of Lord Brahma's hands. He is offering pranams to Krishna, but his hands are rather strangely cocked to the left. This is likely the artist's way of emphasizing Lord Brahma's ontology. In other words, a divine personality with four heads would also likely have unusually manifest arms and hands. We might also see this is an indication of movement in the hands, i.e., each head is offering pranams. We note that the artist has not adorned Lord Krishna with his traditional peacock feather. Instead, we have three rounded, flower-like shapes on the front of Krishna's crown, being somewhat reminiscent of peacock eyes. At the back of His crown are two spikes, which not only mirror the sharp corners of His clothing, but also remind one of long peacock feathers. As we typically see in this style of painting, the artist has allowed certain elements of the scene to creep out over the boundaries of the panel. In this case, the tree canopy behind Krishna's head obviously escapes the bounds of the panel. More subtly, the artist has extended the lines from the sharp corners of Krishna's dhoti and Brahma's shawl into the yellow border below. The way in which these elements escape the boundaries, in my mind, depicts the spiritual world impressing itself upon the material world: this transcendental pastime is reaching out to the viewer, a fallen conditioned soul who gets the mercy of the Lord's pastimes, enacted for the purpose of saving the devotees from entanglement in maya.

| |