|

|

|

|

BY: SUN STAFF

Emperor Akbar and wife Jodha May 30, 2010 — CANADA (SUN) — A serial presentation of the Mughal effect on Vaisnava society. Today we begin what will be a multi-part study of the Mughal emperor Akbar, the son of Emperor Humayun, who died in 1556. Akbar is generally described as the most benign of the six early Mughal rulers, as evidenced by various Hindu temples that were rebuilt or protected under his watch, and social programs he instituted that supported the local citizens in the regions he occupied. We will attempt to show both sides of that argument, but as the reader will see, a significant amount of damage was incurred by Vaisnava and Saivite temples, deities and devotees under Akbar's reign.

Before we begin, however, please note the correction of an error made in Part 9 of this series, in which we gave an incorrect year for Humayun's death. Emperor Humayun ruled from 1530 A.D. until his death in 1556 A.D. His rule was interrupted by a 15-year exile, after which he returned to power in India for one year, until his death. Our thanks to the astute reader who caught the mistake. Emperor Akbar was third of the six early Mughal rulers, following his grandfather Babur, and his father Humayun. Like Aurungzeb, Akbar ruled for a period of 49 years, from 1556 A.D. to 1605 A.D. He came into power at the age of thirteen, and was eventually succeeded by his son, Jahangir, upon his death in 1605.

Jesuits at Akbar's Court Akbar's presence was felt all across northern and central India, from Rajasthan to Bengal. Under his watch, Muslim forces completely destroyed the city of Vijayanagara in north Karnataka state. By 1589, Akbar ruled nearly all of North India. Capturing the fort at Ranthambor, Rajasthan, he ended the era of Rajput independence and soon controlled most of that state. During the infamous siege of Chittor, 8,000 Rajputs along with some 30,000 local Hindu citizens died inside the fort, which was overtaken by Akbar's army. Historians suggest that when Akbar's forces overtook Chittor, the Hindus, citizens from the outlaying areas, were offered religious conversion. When they refused, they were killed. The siege of Chittor was recorded in text and painted illustrations in the Akbar-nama, which will be presented in a future segment. During his reign, Akbar eliminated military threats from the powerful Pashtun (Pathan) descendants of Sher Shah Suri, and at the Second Battle of Panipat he defeated the Hindu king, Hemu. Over the next two decades he consolidated his power, employing diplomacy with the powerful Rajputs in the northwest, and solidifying his rule in Bengal through a campaign whereby wealthy Bengali landowners were made to convert to Islam in order not to lose their family lands. From his seat of power near Agra, Akbar's armies fanned out across the region, from Patna to Orissa. Perhaps fortunate for Bengal, his armies detested the climate of the Ganges delta, and avoided it as much as possible. Service there was often considered to be a punishment.

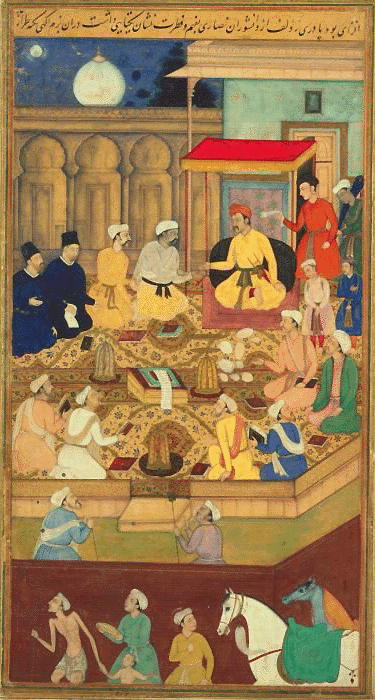

The Court of Akbar, from 'Akbar-nama' Part of Akbar's strategy of management was to utilize resources commandeered in one part of the country, sending them to quell unrest in a distant area. For example, in order to bring local Bengali forces under control, Akbar dispatched the Rajput chief, Raja Man Singh, who had been made a general in Akbar's army. In 1594 A.D., Singh was sent into Bengal to act as Governor. Setting up his own provincial capital in the delta's northwest corner, Raja Man Singh then doubled back, leading a vast army of Akbar's forces into Bhati (Lahore). There are many fascinating aspects of Akbar's presence in Bengal that we'll cover in the days ahead. Akbar's court was very different from the footprint of the Sultanate in Bengal, both in the political, social and religious realms. In fact, by 1595 A.D., the members of Akbar's court in Bengal were primarily ethnic Iranians or Turks, who had migrated into Bengal to take advantage of opportunities in court service, and the rich agricultural lands. Aside from the Islamic influence, these Central Asians infused the local Bengali society with their own culture and art, as well as the Persian influence.

| |