The Miracle Plays of Mathura:

Raslila Troupes of Braj

BY: SUN STAFF

Apr 30, CANADA (SUN) — In his book on the Miracle Plays of Mathura, author Norvin Hein described in great detail the workings of the highly trained raslila troupes found in the Braj area in the late 1940's. "Most of the residents of Mathura District who are professional actors are members of rasmandalis, or troupes for the performance of the raslila. As the devotees know, all of the Lord's activities or pastimes are called lilas, or 'sports'.

On a certain autumn night when the moon was full, Krsna favored the gopis by dancing with them in a circular dance, which the Visnu Purana calls the rasa [1]. The Bhagavata Purana brings the two terms together, calling this original romantic event the rasalila [2]. This dance is re-enacted continually in the most-loved form of sectarian drama. The plays in which the re-enactment is an essential feature are called, in full, raslilanukaran, 'the imitation of the ras sport'; but for convenience the compound is shortened, and the dramas are called raslilas.

A raslila is not a re-enactment of the ras alone. The performance of this dance is always its first element, of central importance because it is a ritual celebration of Krsna's most gracious deed, meaningful to devotees however often it may be seen; but the presentation continues, dramatizing an important supplementary tale as well. Thus, every raslila consists of an initial dance followed by a one-act play based on any one of the multitude of Krsna's lilas. The entire performance receives its name from its prior element, the ras, its most sacred component and its recurrent feature.

The raslila is a drama of which Braj claims the sole guardianship; it is the monopoly of Braj residents because it is the enactment of those lilas of Krsna which he performed in Braj. Krsna performed an infinite number of sportive acts in other regions as well. In heavenly realms he carries on his unmanifest sports (aprakat lilas) eternally in His transcendent form and therefore in a manner beyond human perception and beyond the reach of drama. When by his grace he descended to this world and performed manifest sports (prakat lilas), which are open to human knowledge, he did many of His deeds in Kurukshetra, Dvaraka, and other places far from Braj. These deeds are not enacted in the raslila. [3]

The actors of Braj do not claim them as their special possession. Their responsibility is Krsna's bal lilas, the sports which He did as a child in His own boyhood home. The repertoire of the raslila begins with the celebration of Krsna's birth (the janma lila) and tells His life story as far as His triumph over Kans in Mathura (the Kansbadh lila) and His sending back a messenger to console His childhood friends (the Uddhav lila). And who are more qualified than the actors of the Braj country to present these scenes authentically?

Descriptive writing on the raslila in Western languages [at the time of this writing, c. 1949] - or in any language - is very scare indeed. One cause is the stubborn unintelligibility of the dramas, even when seen, to one who has not been introduced to the raslila's intricate world of special theological concepts and religious symbols. One of the few nineteenth century notices of the raslila is a report in the London Times, March 24, 1959, describing an evening's entertainment provided by a raja for the European officials of Lucknow. The correspondent's one-sentence report betrays the boggling of the Western understanding in the face of the exotic:

"There was one other interlude in the nautch, when there appeared six or eight boys dressed as girls, their faces covered with gold-leaf, who performed an abstruse comedy or mystery, and sang a chorus of an incomprehensible character, from which the company were diverted very pleasantly by an invitation to witness the fireworks from the balconies, verandahs, and the roof of the palace."

This is a classic admission of incomprehension. The raslila is by no means as readily understood as fireworks! Many others may have seen the raslila but failed to write about it because they could not.

The major reason for the scarcity of eyewitness accounts, however, is the protective attitude of its patrons and producers, who are uneasy about how outsiders may interpret the amorous aspects of the legends which the raslila dramatizes. Even at the time of the writing of the Bhagavata Purana there were non-Vaishnavas who criticized the morality of Krsna's relations with the gopis, and the adherents of the Krsnaite sects smart under censure to the present day. They do not wish to give passing strangers any opportunity to sensationalize on the surface meaning of these lila pastimes if they lack the time and inclination to seek an understanding of the theological interpretation of those tales. [Nor, of course, do they wish to allow uninformed neophytes to unwittingly commit offenses to the Lord.]

The Raslila Troupe

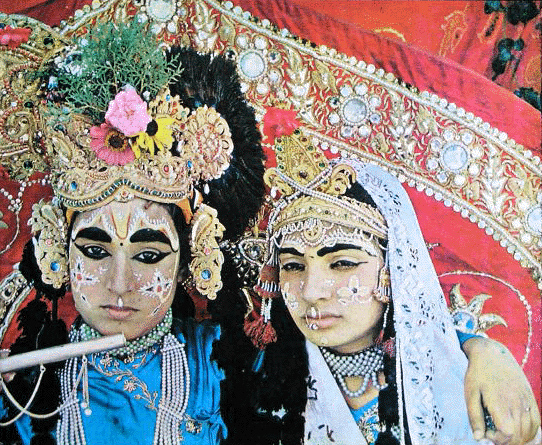

If the raslila can be said to be the property of the residents of Braj, then its custodians are the masters of the rasmandalis or troupes of actors of the raslila. The master of such a troupe is called 'swami' or sometimes 'rasdhari', although this latter title can be extended to the other adults of his troupe also, or, in the plural, to the entire troupe collectively. Because of the extreme youth of most of the performers, the quality of the raslila is entirely dependent upon the sensitivity and skill of their trainers. In 1940 there were some twenty of these directors who were prominent captains in their profession.

The swami is the proprietor and undisputed master of his troupe. The artists at his command must number at least ten. The first necessity is an orchestra (samgit samaj) of at least four instrumentalists to play the sarangi, the drums (tablaor mridanga), the cymbals (jhanjh), and the harmonium. There must be svarups to impersonate Radha dn Krsna, and four actors to take the role of the gopis. Prosperous troupes may add players of a second harmonium and a second sarangi, a costumer and cosmetician (sringari), and even a tutor for the children of the company. Swami Muralidhar Bohre of Vrindaban travels with a troupe of seventeen.

All swamis without exception are literate in Hindi and are able to recite Sanskrit verses. Swami Kishen Lal is unusual in being able to read the Bhagavata Purana in Sanskrit with comprehension. Swami Ram Datt and Swami Megh Syam, the most advanced in formal education, have the equivalent of a high school diploma.

The child actors must be literate in order to learn their lines efficiently. If any boy is unable to read when taken into a troupe, the swami teaches him or has him taught to the necessary level of proficiency. Thereafter the young actor's training is almost entirely in the texts of the plays. This specialized professional education produces youths who are steeped in the poetry of the Krsna cult but who lack most of the elements of a general education. Social reformers have often criticized the raslila for its disorganization of the education of talented children.

Boys are recruited at the age of eight or ten. They usually begin their acting careers as impersonators of the gopis. If they have good voices, good memories, and good looks, they may be promoted at the age of eleven or twelve to the roles of Radha or Krsna. Puberty brings their careers to an end. Most are then forced into an outside world for which their training has prepared them poorly. Those who have special musical talent sometimes remain in a troupe as instrumentalists and vocalists in the samgit samaj. A few who have carefully memorized or written out all their master's dramas succeed in founding troupes of their own if they have in addition some savings, initiative, and organizing ability. Each 'graduating' actor is a potential swami.

Every swami would, of course, like to have his own son as his leading actor and ultimately as his successor. The universality of this aspiration is manifested in the frequency with which one sees toddlers playing about among the instruments or the orchestra at performances. The hope is that these small boys will absorb the dialogues and the spirit of the profession. At the end of infancy each will have his try at the stage by tripping the dances as the smallest of the gopis. Ability is such an important requisite, however, that the hereditary principle cannot operate fully. A few families of Karahla continue to be represented among the rasdharis after the passage of a hundred years, but in general the list of sub-castes and of villages which are famed for activity in the raslila has undergone great changes during that time. This is due to the fact that a swami must often turn, for the effective filling of important roles, to the children of distant relatives or of strangers.

Actors who are not members of the swami's family are engaged at an agreed monthly wage, sent regularly to their parents. Children must be given a vacation with their parents during the hot season of May and June. The earnings of actors range from Rs 25 monthly for the lesser gopis to Rs 100 or more for a popular impersonator of Krsna in a famous troupe. The swami who must meet this payroll and train, house, and feed this band is the manager of a complex business enterprise.

The Raslila Stage

The raslila's own special stage is a circular platform of stone or concrete, standing three feet or less above the level of the ground, and broad enough to provide dancing space for eight persons in a roomy circle. Such a dancing-platform is called a rasmandal. (The name is applied also to the circle of dancers and to the circular dance seen in the performances.) These stages stand out-of-doors, wall-less, and open to the sky.

The form of the stage reflects the importance of the circular dance as a component of the raslila. The rasmandal provides a smooth round masonry floor, broken only at one margin by a dais (rangmanc) on which Krsna and the gopis rest during certain rituals and in the intervals of their dance. When, as at Vrindavan, the stone floor is exceptionally broad, spectators wit on mats on the outer border of the platform itself. At smaller installations the audience is accommodated wholly or mainly on the surrounding earth. So far as the author knows, this circular stage is peculiar to the raslila. In theory these rasmandals are built only in spots where Krsna Himself once danced the ras. Hence almost all of them are found in Braj at the stations of the banjatra pilgrimage trail which meanders to the scenes of Krsna's major exploits. In all other places where the raslila may be performed, rasmandals are not available, and a stage is improvised.

The usual setting is the courtyard of a temple or the home of a wealthy Vaishnava householder. In a private home the playing-space is laid out on a wide veranda or in a living room or inner courtyard or grassy garden nook. Because the onlookers sit on the floor or earth and seldom number more than two hundred, a raised platform is not necessary in order to maintain visibility. The stage is merely a large white sheet, put down atop a coarse matting of cotton or jute.

Everything needed for furnishing this Vaishnava theater can be carried in one trunk. The essentials are the floor coverings mentioned, a smaller cloth for use as a curtain, and a few bright and rich spreads for a royal seat. The other requirements can be improvised from the furnishings of any middle-class Hindu home. The one necessary piece of stage furniture is a dais with a throne (sinhasan) erected upon it. So a takht is brought - the hard wooden bed which people sleep on in the humid rainy season. It is placed at the rear edge of the spread-out floor covering. Draped with cloth, it becomes the rangmanc or dais. This small platform is used only as a base for the throne of the Deities and as a sitting place for the gopis who cluster around Their feet. The double-seated throne which is raised on it often consists of two chairs placed side by side, or even a bench, covered with the most luxurious cloths available. On this dais the svarups, surrounded by the gopis, always present Themselves in formal pose for the worshipful gaze of the audience at the beginning and end of each performance."

In our next segment on the Braj raslila troupes we will at stage props and paraphernalia, costumes, the role of audience, and the distinct elements of both the ras and the lila aspects of a performance.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Jivananda Vidyasagara, ed., Vishnupuranam, V. 13.47-55, p. 532.

[2] Bhagavata Purana, III.2.14.

[3] The one exception is the Sudama lila, which is set in Dvaraka, but it is the story of Krsna's relation with a childhood friend.